MARIA ROMANOV: GRAND DUCHESS MARIA NIKOLAEVNA OF RUSSIA

by Amanda Madru

June 14th, 1899 (O.S.). A 101-gun salute is fired from the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg, heralding the birth of yet another daughter to Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia, and his German-born wife, Tsaritsa Alexandra Feodorovna. The baby’s arrival is met with near-universal disappointment: the Pauline Laws implemented by her ancestor, Emperor Pavel I’s stipulated that males come first in the succession, and a male heir was eagerly awaited. Nicholas and Alexandra have, after nearly five years of marriage, only three little girls to show for themselves. Russia is in need of an heir, and the Imperial couple has once again failed on this count. The infant is named in honor of her paternal grandmother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna. She is christened Her Imperial Highness the Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna of Russia.

Little Maria grew into a sweet-natured child with blue eyes so large that they were known in the family as “Marie’s saucers” (Massie, Robert K. Nicholas and Alexandra, 133). Her great-aunt, Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Saxe-Coburg, likened her to “…one of Botticelli’s angels” (Rappaport, Helen. Four Sisters, 53), and her cheerful disposition led her great-uncle, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, to nickname her “The Amiable Baby.” (Eager, Margaret. Six Years at the Russian Court). Her governess, Margaretta Eager, was especially fond of her, writing that Maria “…was born good… with the smallest trace of original sin possible.” (Eager) Her reputation for goodness was such that it was rather surprising when Maria stole some biscuits at teatime, Eager and the Empress thought she should be sent to bed, but the Emperor disagreed, saying that he “…was always afraid of the wings growing. I am glad to see she is only a human child” (Eager).

Human though she was, Maria was so mild-mannered that her two elder sisters, Olga and Tatiana, frequently took advantage of her kindness. They excluded her from their games and teased the childishly plump Maria, calling her “fat little bow-wow” (Gilliard, Pierre. Ten Years at the Russian Court and her younger sister Anastasia (born 1901) tended to overshadow the “Amiable Baby” with her exuberant, effervescent personality.

On one occasion, Olga and Tatiana were playing house, and they excluded poor Maria, telling her she could be their footman and that she must remain outside. Maria, however, refused to be the footman. She took her leave, only to return moments later, arms laden with toys, saying “I won’t be a footman. I’ll be the kind good aunt who brings presents.” Olga and Tatiana guiltily admitted that they had been cruel, and from then on looked upon “Mashka” with new respect, although they continued to behave as typical older sisters. When she was ten years old, her fourteen year old sister Olga persuaded her to write to their mother with the request that Olga be given her own room and permission to let down her dresses; the innocent Maria even attempted to convince the Empress that the idea had been her own.

The two eldest grand duchesses were known as “The Big Pair,” while Maria and Anastasia were “The Little Pair.” With the birth of the long-awaited heir, Tsarevich Alexei, in 1904, Maria became the middle child. She may have been one half of the Little Pair, but she may have felt left out due to Anastasia’s bond with their younger brother. Nevertheless, each “Pair” of grand duchesses shared a room, dressed alike, and spent much of their time together, but due to their sheltered upbringing and relatively minor age differences, the four sisters together were unusually close.

Their French tutor, Pierre Gilliard, even wrote in his memoirs that they signed their letters collectively as “OTMA,” and so history has come to know the Romanov girls as a singular unit.

Maria was undisputed sweetheart of the family, but as she left childhood behind, many who knew her also came to regard her as the beauty. Tatiana was considered the most elegant, but it was Maria, with her big blue eyes, full lips and lustrous brown hair who won the heart of her cousin Louis “Dickie” Mountbatten. “I was determined to marry her,” wrote Lord Mountbatten. “You could not imagine anyone more beautiful than she was!” Of course, Dickie’s dream did not came true, but he never forgot Maria—he kept her photograph beside his bed until his own assassination in 1979 (King, Greg. Wilson, Penny. The Fate of the Romanovs. 49). Gleb Botkin, son of the family doctor, also described her as the most beautiful of the four sisters. She was “…admittedly the prettiest of the four—a typical Russian beauty, rather plump, with cheeks red as apples” (King, Wilson 49).

Many others, including tutors Charles Sydney Gibbes and Pierre Gilliard, and family friends Anna Vyrubova, Sophie Buxhoeveden, and Lili Dehn expressed their admiration for the appearance of the third Romanov daughter. One of the imperial infirmary nurses , S.F. Ofrosimofova observed with particular eloquence, that Maria was “… tall, healthy, with sable eyebrows and a bright blush on her open Russian face; she was especially lovely to a Russian heart… her eyes illuminate her entire face with a unique, radiant luster; they sometimes seem black, as long eyelashes throw shadows over the bright blush of her soft cheeks. She is merry and alive, but she has not yet awakened completely to life; probably concealed in her are the immense forces of a real Russian woman.”

In some instances, beauty may be skin deep, but this cannot be said of the placid Maria. She was unaffected and genuine. Imperial titles meant little to her, and she took great interest in the lives of others, including soldiers and servants. Nurturing came by her naturally, and so she was the one who most frequently remained behind with her ailing mother and hemophiliac brother while the rest of the family went off on various adventures. Like her sisters, she had innocent flirtations with some of the young sailors on the Imperial yacht Standart, and her childhood love of soldiers transformed into a romantic—albeit impossible—dream of marrying an officer and having a large family; indeed, it was said that, had she not been a daughter of the Emperor, she would have made “some man an excellent wife” (Massie 133).

The idyll of Maria’s childhood and the grandeur of the 1913 Tercentenary of the Romanov Dynasty passed into memory with the beginning of the First World War. As all of Russia mobilized, the sheltered Imperial daughters were forced to grow up very quickly: hospitals were opened at Tsarskoe Selo, and Olga and Tatiana, along with Empress Alexandra, trained to become Sisters of Mercy, but Maria and Anastasia were deemed too young to be nurses. Nevertheless, the Little Pair were patrons of their own hospitals. They regularly visited and cheered “their” wounded soldiers by playing games with them, sharing their personal photo albums, and asking them questions about life outside the palace walls. The soldiers were initially shy around the grand duchesses, but it did not take long for the easygoing Maria to put them at ease.

It did not take long for one especial officer became the object of Maria Romanov’s affections. The grand duchesses and their mother would sometimes visit the Emperor and Alexei at Army Headquarters in Mogilev, and it was there that Maria fell in love with Nikolai Dmitrievich Demenkov. Although her mother and sisters teased her affably about her feelings for “Fat Demenkov” (Rappaport 240), who was indeed on the chubby side, Maria adored him. She called him her “dear Demenkov” and addressed him by the Russian diminutive “Kolya,” and when she wrote to her father at Stavka, she jokingly signed her letters as “Mrs. Demenkov.”

The exhilaration of this impossible crush was soon overshadowed by bad news from the front, which made Maria and the rest of the family fear for their father. The war effort was not going well, and Nicholas II made the fateful decision to take command of the army despite his inexperience with such matters. As the mismanaged war placed a terrible strain on the tsarist government, mass shortages and hunger became pervasive, and civil unrest spread throughout the country. By early 1917, the Emperor had lost first the support of the people, then of the soldiers, and finally of the Duma, and in a dramatic culmination, he was finally forced to abdicate. The Revolution was now in full swing.

In a tragic twist of fate, the Romanov children contracted measles at this time, and because they were too ill to be moved, the brief window of time in which the family could have been evacuated to England became closed (Rappaport, Helen. The Last Days of the Romanovs, 148). The Empress and her stricken offspring remained cosseted at the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo, awaiting the return of the Emperor by train from Mogilev, while riots erupted in the streets of the city now known as Petrograd. While three of her siblings were seriously ill, the hardy Maria and Anastasia had thus far remained healthy, but the burdens Maria carried were enormously taxing: “Alexandra received Viktor Zborovsky, one of the most trusted officers of the Escort guarding the palace… As Zborovsky was leaving Maria stopped him and they ended up chatting for an hour. He was deeply moved by the great change in her during recent days. ‘Nothing remained of the former young girl,’ he told his colleagues later; in front of him stood ‘a serious sensible woman, who was responding in a deep and thoughtful way to what was going on.’ (Rappaport, Helen. Four Sisters 291).

In spite of her bravery, it was clear to family friend Lili Dehn that Maria was under a terrible strain, the pain of which she was concealing for the sake of her mother. Dehn overheard someone weeping, and when she went to investigate, she found “In one corner of the room crouched the Grand Duchess Marie. She was as pale as her mother. She knew all… She was so young, so helpless, so hurt” (Rappaport 291). Maria was, according to Dehn, terrified that “they” would come to take her mother away.

The situation outside the gates of Tsarskoe Selo spiraled out of control. The regiments mutinied, murdered their officers, and left their barracks, while the family was unable to contact their absent husband and father. The angry mob came closer and closer; although 1,500 Cossacks remained to protect the palace (Massie 431), they were warned that the rebels were fast approaching, and it wasn’t long before a sentry was shot less than 500 yards away as the echoes of gunfire grew ever closer. Alexandra, watching the scene from above, decided to go out and speak to the soldiers, heedless of the great risk to her safety. She was accompanied by her courageous third daughter, Maria.

Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden recalled the image as “…unforgettable. It was dark, except for a faint light thrown up from the snow and reflected on the polished barrels of the rifles. The troops were lined up in battle order… the first line kneeling in the snow, the others standing behind, their rifles in readiness for a sudden attack. The figures of the Empress and her daughter passed from line to line, the white palace looming a ghostly mass in the background (Massie 432).” Alexandra’s best efforts notwithstanding, the loyalty of the remaining troops quickly eroded, and they soon abandoned the family they had sworn to protect. Worse, the Little Pair was coming down with the measles, and it was then that the Empress learned of her husband’s abdication.

Perhaps because of her exposure to the frigid nighttime air, Maria was hit hardest by the illness. Although her mother and Lili Dehn nursed her tenderly, her temperature soared, and she developed pneumonia in addition to the measles. As her fever hit 105 degrees Fahrenheit, doctors administered oxygen (Rappaport 309), and Alexandra sent for Anna Vyrubova, fearing that her daughter was dying. Somehow, though, Maria pulled through, but it was not until mid-March that the fever subsided and she began to recover; it took much longer for her to fully regain her health, and she remained very weak for some time. When she was deemed well enough, Maria was finally told that she was no longer a Grand Duchess, but a plain Citizeness Romanov.

The family remained imprisoned at the Alexander Palace for most of the summer of 1917. Guards of the Provisional Government now stalked the Alexander Palace halls, but Maria’s daily routine changed little until word came that the former Imperial family would be sent into exile. They had hoped to join their relatives in the Crimea, but upon learning that they were to pack warm clothing and prepare for a five day ride by train, Nicholas deduced that they were being taken to Siberia (Rappaport 317).

After an emotional and incognito departure from Tsarskoe Selo and a long journey into the unknown, the Romanovs and their faithful retainers arrived in Tobolsk, where they would take up residence at the Governor’s Mansion. The always cheerful, adaptable Maria remained optimistic, befriending the guards and noting to Charles Sydney Gibbes that she would be quite content to remain in Tobolsk forever, if only they were permitted to walk into the town. The children amused themselves by looking at their old photo albums, play-acting, reading, playing games, and working. They chopped wood and cleared snow from the yard as well as the steps and roofs of the outbuildings. Once, one of the commissars observed Maria digging with a broken shovel. He inquired as to why she had not asked for a new one and remarked that he had not thought she would have wanted to perform manual labor. “But I love this kind of work,” she replied with surprise (Rappaport 337). As long as they could work outdoors, Maria and her family seemed happy and content.

Peace for the Romanovs did not last. In October, Lenin and the Bolsheviks overthrew Alexander Kerensky and the Provisional Government, and it wasn’t long before the daily difficulties the family faced increased exponentially. The postal system was unreliable and their correspondence was strictly monitored, so they had very little contact with the world outside, and the cold was intense, even within the Governor’s Mansion—out of necessity, they wore their warmest clothing throughout the winter. Still, they passed a relatively happy Christmas, celebrating with a Balsam fir and exchanging small, handmade gifts, and to their great joy, they were even permitted to attend religious services at the nearby church.

Through the dark, depressing days of the winter of 1917-18, Maria remained cheerful and loving. Even the commissar and the guards grew fond of her, as observer Klavdiya Bitner regarded her as “…kindhearted, cheerful, with an even temper, and friendly” (Rappaport 349). In February, things got worse, as the Special Detachment guards were sent away and the new Red Guard revolutionaries arrived. They dismantled the snow mountain the children had built and forbade Nicholas from wearing his epaulettes, while new financial restrictions gave the family no choice but to release some of the retainers who had accompanied them to Siberia, though some volunteered to remain without pay. There was a distinct hardening in the sentiments of the guards toward the former Emperor, as well as his wife and children; there was no avoiding it. “The atmosphere around us is fairly electrifying. We feel that a storm is approaching,” Alexandra confided to Anna Vyrubova. Indeed, the instincts of the former empress proved to be spot on.

Soon, orders stated that Nicholas was to be sent away, presumably to Moscow to stand trial, and Alexandra felt it was her duty to accompany her husband, but Alexei was still recuperating from a bleeding episode and was too ill to travel. Four of the five children were to remain in Tobolsk: sensible Tatiana, “The Governess,” was the leader, and so she would need to look after her ailing brother, as well as the moody, depressed Olga, and Anastasia, who was still considered a child. That left only the strong, capable Maria to travel with her parents into the unknown.

Artist’s depiction of Maria Romanov’s arrival at Ekaterinburg with her parents.

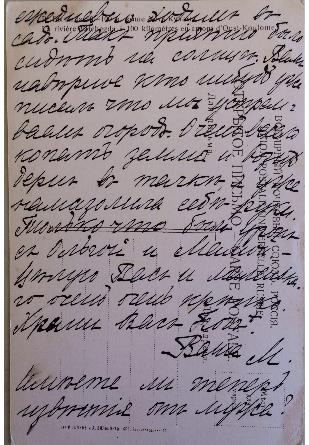

After bidding the others a tearful goodbye, Nicholas, Alexandra, and Maria began their uncomfortable trip to Ekaterinburg, an industrial city in the Urals known to be hostile to the Emperor. They were to be quartered at the house of a merchant named Ipatiev, but the Reds referred to the dwelling by the rather ominous moniker “The House of Special Purpose. Life here was even more restricted. The Romanovs were prisoners, and they had to make do with prisoners’ rations. Maria wrote to her siblings: “I miss our quiet life in Tobolsk. Here there are unpleasant surprises every day” (Rappaport 363). They were not permitted to walk outside or work in the garden, nor were they allowed to receive visitors. Nicholas could no longer read his newspaper, so they had no idea what was going on in the world at large. Languages other than Russian were strictly forbidden. Worst of all, they had to settle for abbreviated religious services.

Olga, Tatiana, Anastasia, and Alexei arrived to join their parents and sister after a harrowing voyage from Tobolsk. After the initial joyful reunion, though, the family’s living conditions deteriorated even further. The whitewashed windows remained closed to fresh air, a wooden fence was installed so they could not view the street, their belongings were pilfered by intoxicated guards, and they even had to ring a bell to use the toilet. They had no privacy to speak of. Maria, as always tried to make the best of it. She attempted to befriend the guards, some of whom responded to her overtures because she did not have the “air of grandeur” they had expected in a daughter of the hated Emperor. However, one guard recalled an incident when someone told a dirty joke; while Tatiana ran from the room “pale as death,” Maria looked at the guard and asked, “Why are you not disgusted with yourselves when you use such shameful words?” (King and Wilson 242). The privileged, sheltered Maria had become a young woman of tremendous inner strength.

Soon after, Commandant Yakov Yurovsky arrived, and daily existence in the Ipatiev House became even more difficult. Unbeknownst to his prisoners, Yurovsky had orders from Moscow to “exterminate” them, but the family did sense a change in the guards’ attitude toward them. Perhaps they suspected, for when they were granted a full Obednya on July 14th, the deacon sang the prayer “At Rest With the Saints,” and the family broke custom and fell to their knees. Three days later, the early morning hours of July 17th, Maria Nikolaevna Romanov would be murdered along with her parents and four siblings in a Ekaterinburg cellar. She had just turned nineteen.

More about Maria Romanov in the book MARIA and ANASTASIA: The Youngest Romanov Grand Duchesses In Their Own Words: Letters, Diaries, Postcards.

One thought on “MARIA ROMANOV: GRAND DUCHESS MARIA NIKOLAEVNA OF RUSSIA”

Very Sad for what may have been.

Greg Westen